They Say She’s Different: Farewell to Betty Davis, the First Lady of Funk

Betty Davis has passed away, and the world will never be the same. Rarely does the news of a celebrity death touch me to my core. But Betty’s death hits different. People will remember Betty as the original nasty gal, as a pioneer of punk, funk and rock n roll. As an incredibly talented, creatively independent, jaw-droppingly gorgeous woman. We all know that she was ahead of her time, and an inspiration to artists from Prince to Ice Cube to Erykah Badu. Jimi Hendrix, Santana andSly Stone were her friends, Miles Davis, Hugh Masakela and Eric Clapton her lovers. Yet Betty was also a woman up against the world, a world that constantly sought to shame her body, dull her mind and squash her soul. We black women of the 21st century, into indie culture, already know complexities of the struggle to find an identity. Betty, a black woman who defied genre, experienced more push back than many women would have. Fame wasn’t the point. Freedom was.

I was seventeen when I first heard her music. I felt at odds with myself and everybody else. I felt like I was seeking something that the 21st century just couldn’t provide; everything polished, everything pristine, everything perfect, everything pop. I wanted something as raw as the ache that was as persistent and pulsing inside of me. Then I found Betty. In her I found a friend, and a mentor; someone who railed against the mundanity and monotony of modernity. My generation, I felt, was already jaded by rapid developments of technology and the internet was all tumblr and teenage woes. I wanted none of that, and more of whatever it was that Betty was bringing. Her gaze was direct and energetic. She didn’t pout, or look downcast at the camera. She looked straight at the camera, completely unabashed, daring you to say something, do something, crazy.

She embodied an unusual but powerful politic. Fearless, she was a potent combination of raw sexuality and brazen intelligence, but also of humour, wit, humility and hubris. And bubbling up from beneath her beautiful surface, there was a bewildering fury. In her lyrics and the wild catercall of her voice I found hope, excitement and a source of inspiration. It was something different, something strange. Supersonic.

They say I’m different ’cause I’m a piece of sugar cane

Sweet to the core that’s why I got rhythm

My Great Grandma didn’t like the foxtrot

Now instead she spitted snuff and boogied to Elmore James

…

That’s why they say I’m different

And that’s why they say I’m strange

Betty was more than a singer. She was a trailblazer, not just of music and fashion, but of social politics. In her own right, and by her own admonition, she was “a political girl” and she practised what she preached. Her version of Cream’s “Politician” feels less of a cover and more of an original statement; she slightly modifies the lyrics to emphasise her sense of agency and control.

Hey now, baby

Get into my big black car

I wanted to show you

What my politics are

I’m a political girl

And I practice what I preach

I support the women (I like you, girls)

Though I’m leanin’ to the right (Got to have a man)

I support the women

Though I’m leanin’ to the right

But I miss nothin’ when it comes to a fight…

The lyrics are the same — mostly. She changes them in some important places. I support the left/ Though I’m leaning to the right becomes I support the women(I like you, girls)/

Though I’m leanin’ to the right (Got to have a man). And, but I’m just not there, when it’s coming to a fight becomes but I miss nothin’ when it comes to a fight.

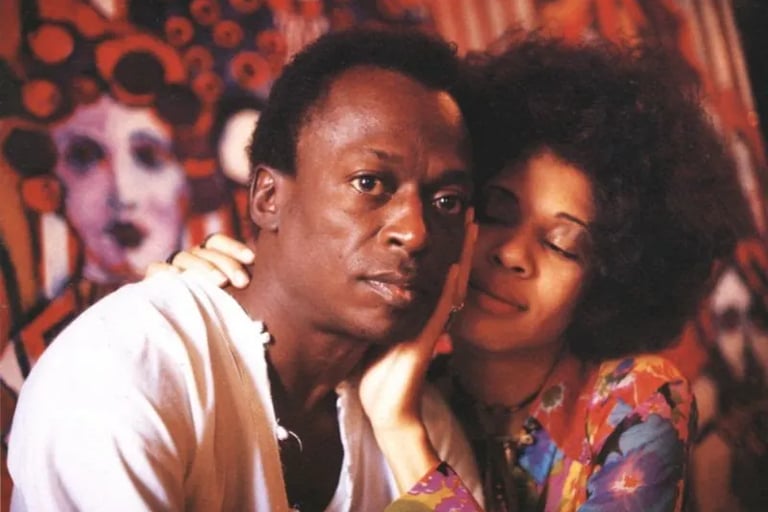

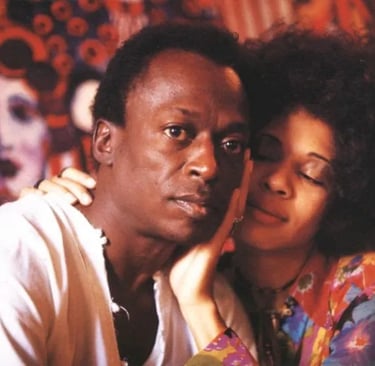

Betty’s new lyrics show a commitment to direct action, and Betty’s activism could be enacted anywhere — in the streets, beneath the sheets, in the studio, on the stage. Betty’s activism had no location, but was in fact defined by freedom of the spirit. Life must be lived on your own terms, and Betty certainly lived hers. You always ride with Betty, and she is always in control of the motor. And she is here for both women and men. Some people might call Betty a feminist, but I wonder what she thought about that word. Betty was no good girl, but a whorey angel, with an attitude to romantic relationships that was, at the time and probably still today, controversial. (She allegedly seduced Miles away from Cicely Tyson). Fifty years before SZA was singing about taking her turn on the weekend, Betty pressed the issue.Her views on romantic partnership are best expressed in her own words:

Your man, my man, what does it mean?

You care, I share, who’s to blame

He’s your man, he’s my man, it’s all the same

’Cause he’s yours, all yours, when he’s there

He’s mine, I have him, when he’s here

You cry, I sigh, what does it mean?

…

You believe, he deceives, who’s to blame?

He’s your man, he’s my man, it’s all the same

’Cause you need him, you please him

When he’s there

I free him, I release him, when he’s here

You love him, I love him, what does it mean?

Betty straddles that thin and dangerous line; was she a feminist who was concerned with women’s rights with a direct focus on smashing gender norms, or was it that she understood the complexities of masculine and feminine energies, both rejecting certain sexual stereotypes whilst embracing others? The answer is not simple. Interviews with a young Betty at the beginning of her marriage were gushing, vowing to love Miles forever and to stay “in the background” as she supported his work. She was only 22. Her perspective clearly shifted. A woman like Betty is the main event, not a support act — figuratively and literally. Her performances were so awe-inspiring that KISS apparently wouldn’t let her open for them, fearing she’d steal the show.

Regardless of what you think of her, one thing is certain; Davis was political, and the politics she preached was one of pleasure, power and personal freedom. The fact is, sexual liberation is not simply a physical freedom. It’s the power to create your own reality, which Betty did with fervour. We see a beautiful woman and we want her beauty to be the source of her creative energy, because we want to reduce her to something tangibly superficial. Yet for a beautiful woman like Betty, in order to get free, you simply cannot use your beauty alone. It can be a tool to get what you want, but if over-relied on, it has the potential to hinder, not help, your search for liberty. I think Betty was very much aware of that. At the end of the track, you can hear her screech at her husband Miles’ assertion that she should overdub the track. It’s a cry of retaliation. Of their marriage, Betty said “every day married to him was a day I earned the name Davis.” Miles was known to have been an extremely abusive man, and they divorced after just one year of marriage. In the (rather thin) documentary about her life, Betty recalls:

“I told no one of how Miles was violent . . . . So I wrote and sung my heart out. Three albums of hard funk. I put everything there. But doors in the industry kept closing. Always white men behind desks telling me to change — change my look, change my sound . . . . I needed to ‘fit in,’ or else no contract . . . . I learned that stars starve in silence.”

These words tell us that Betty, and let us never forget it, was a survivor. It’s a testimony to her that, despite a marriage to a talented yet abusive musical genius, she carried on making powerful music under her own terms. The technicolour world that swirled around her was filled with darkness and pain. While Betty herself famously didn’t use drugs, alcohol or even smoke cigarettes, virtually all of her friends in the music industry did; it was, after all, the era sex, drugs and rock n roll.

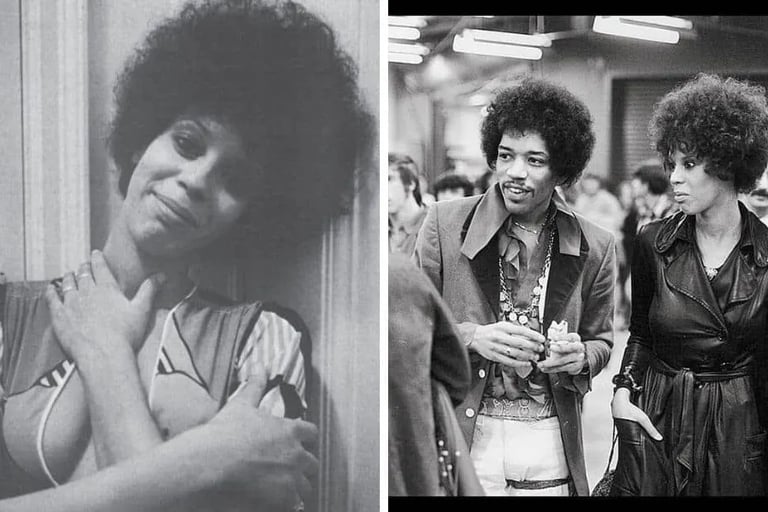

One of Betty’s best friends was Devon Wilson, a gorgeous “supergroupie” who was a long time girlfriend and confidante of Jimi Hendrix. In an interview, titled Cop of the Year, with Rags magazine, Devon spoke of her fling with Mick Jagger, which at the time was hot topic:

“He likes either fourteen year old girls who look like little girls or thirty year old women, except me (Wilson), of course. I think he’s into a heavy spade trip, which had a little something to do with us.”

Betty’s song, Steppin in her I. Miller shoes is about Devon and her tragic story. Catchy and melodically upbeat, I. Miller Shoes is in fact a song about sexual violence. It is truly radical, an apoplectic insight into society’s violent treatment of women told through the medium of funk.

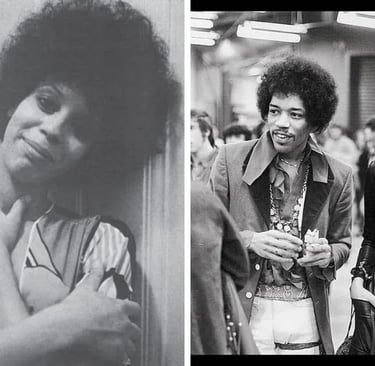

Devon Wilson, and Wilson with Jimi Hendrix

Devon was suffering from addiction and died in mysterious circumstances, falling from the 8th floor of a Chelsea hotel. It remains unclear whether it was a suicide or homicide. However, whatever happened to Devon, Betty knew that ultimately the perpetrator was society; a society that perpetually harmed women, and in particular, black women:

Music men wrote songs about her

Some sad, some sweet, some said were very mean

Rock music played loud and clear for her

Rock music took her youth and left her very dry

She was used and abused by many men

He’ll tell her why

Tell her!

Tell her!

…

And when they told me that she had died

They didn’t have to tell me why or how she’d gone

I knew!

I knew!

Devon Wilson, Miles and Betty Davis at Jimi Hendrix’s funeral

A woman exercising her autonomy with urgency and passion scares people. A woman with a strong sense of herself is a woman vulnerable to the jealousy and venum of others. Betty never deferred, for any substantial period of time, to the manipulation, control and coercion of her image and career by a man. This choice eventually destroyed her career, but Betty couldn’t be bought, couldn’t be sold. Betty was loved and even worshipped in her own time, but when it came to the crunch, she was thrown under the bus by those who should have supported her. The National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) told the black community to boycott her music because she was too sexual, and didn’t act, look or sound like a sophisticated black woman should. Her lovers, from Miles to Eric Clapton, were ultimately terrified of her and turned their backs, worried that she would eventually outshine them. Her record labels abandoned her because she wouldn’t soften her image or sign contracts that would have disenfranchised her from creative independence. She was a maverick, and she paid a heavy price for her difference.

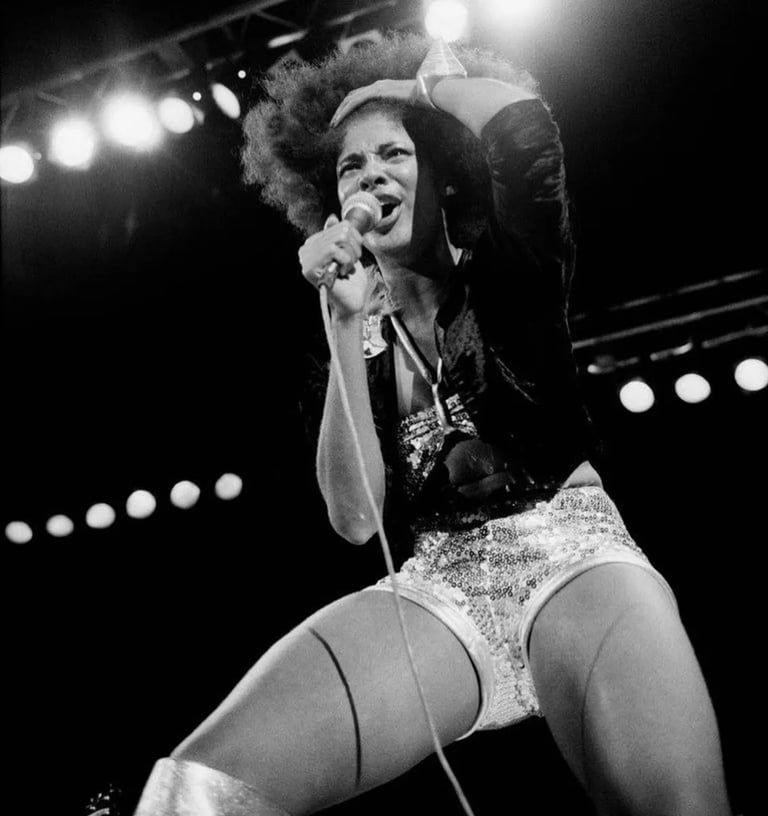

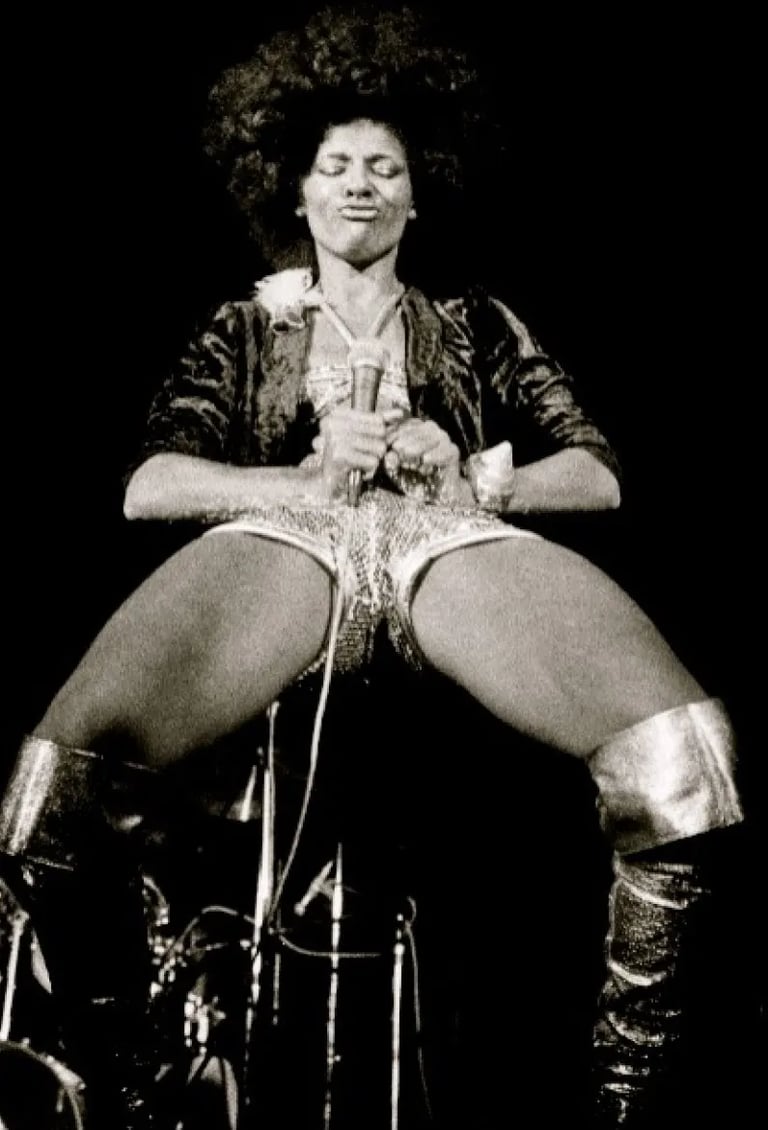

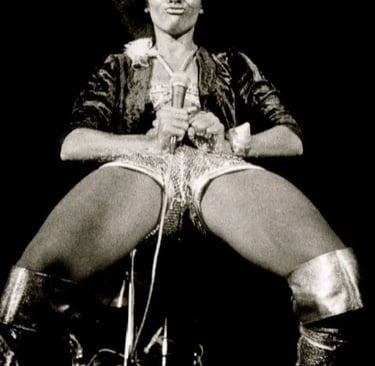

There is very little footage of Betty, aside from one remarkable yet devastatingly short, less than a minute, of her performing I. Miller Shoes live. I like to think that this is because, when people saw Betty perform, they forgot everything else. They may have brought their cameras, but once they saw her step on the stage, with her wild afro, her long legs clad in nothing but the silver boots and the sparkling hot pants, and then, when she opened her mouth, that guttural scream like a cat in heat, a woman on fire, they stopped in their tracks. They forgot to press play, because they had never seen anyone like Betty before. A woman, unchained, unbound. A woman who was truly free. Her track Nasty Gal speaks to those who couldn’t cope with her eroticism — an eroticism that, despite her obvious physical and sexual power, was more spiritual than it was material, creative than it was corporeal:

I ain’t nothin’ but a nasty girl now

..

I said, you went around tellin’ everybody

Yeah, you just put me down now

You dragged my name in the mud

All over town

I’m gonna tell ’em why

You said I didn’t treat you, I didn’t know you

I didn’t love you well

But you know you lied

Yes, you did, I used to leave you hangin’ in the bed

By your finger nails screamin’ (tell the truth, tell the truth!)

Betty scared people. After writing and producing three albums, she fell into an obscurity that, if the documentary about her life tells us anything, was largely self incurred. Disillusioned by a world that wasn’t ready, she retreated from public life, leaving a legacy for future generations to discover her music.

The thing is with being different — it’s a lonely place. You have to be strong, and you have to know yourself.

Authenticity is a rare quality, and people are unsure of how to behave around it. Betty was many things, a paradigm shift, embedded in the past whilst simultaneously living in a time long after the existence of her physical body- an ancestral flame, fuelled by the fires of future freedoms. I often wish that I belonged to Betty’s generation, you know, that feeling of being born in the wrong generation. But we have a tendency to romanticise the past. The 1960s and 1970s seem incredibly exciting, but sexual liberation came with a heavy price. Betty would have seen racial and sexual violence mixed with substance abuse and mental health. There would have been little support for her or her black female friends who struggled to assert themselves in an industry dominated by men.

As a black woman raised on funk, rock and alt culture, as a sex worker performing sexuality and as a performer deconstructing it — Betty speaks to me. I am devastated she is gone — it was always a dream of mine to perhaps one day meet her. But that dream has died with Betty. Instead, I will continue to celebrate her in my work, in my art, but above all, in the way I live my life. I will strive, as Betty did, to be authentic, to be brave, and to be bold.

Rock on, Betty. You will be missed, but never, ever forgotten.